US-led sanctions have devastated Iran’s automotive industry, disrupting its supply of components and causing production to fall. Automotive Logistics assesses the damage

Iran’s automotive industry is, to put it mildly, in some difficulty. Traditionally by far the biggest regional automotive market and production location, it is now operating on a much-reduced scale in the face of US-led sanctions against the government – and there is no realistic prospect of this changing in the short term.

In 2017 Iran made over 1.5m vehicles, 14% more than in 2016. Now, production is declining rapidly, with fewer than 1m vehicles made last year, and production in 2019 is expected to fall by at least 20%, and quite possibly more than this. Sanctions have led to the effective end of PSA and Renault’s supply of parts and technology to Iran-Khodro (IKCO) and Saipa, the two companies which have for many years been the mainstay of vehicle manufacturing in the country.

Falling production has in turn led to a notable lack of supply and choice of vehicles for potential consumers to buy, in parallel with wider problems facing the Iranian economy as a whole. With the economy close to imploding and large numbers of consumers seeing their spending power reduced, the government has attacked the automotive industry for failing to supply the market.

Iran made over 1.5m vehicles in 2017, 14% more than in 2016. By 2018 this had dropped under 1m; this year, output is predicted to decrease by 20%

In July, the Industries Ministry accused the car companies still manufacturing in the country of hoarding vehicles, pushing up prices. Aerial photos of dust-covered cars were published, with IKCO and Saipa said to be the worst offenders. Reports have suggested that 160,000-300,000 vehicles are in storage, although whether all of them are fit for sale is open to doubt. It is thought that tens of thousands of vehicles have also left the production lines lacking key components.

As there are fewer vehicles available to buy, prices have begun to rise. The cheapest vehicle on sale in Iran is the Pride, made by Saipa using old Kia technology. It now costs 510m rials ($12,200) compared with 200m rials a year ago. Government-approved price rises in late 2018 saw ex-factory prices rise by at least 50%, and in some cases by 130%. However, fearing negative public reaction, the government has now reacted by introducing new regulations which require car manufacturers to report production costs, profit margins and the final price to the country’s Competition Council. Company managers who fail to comply face two-year prison sentences.

From revival to ruin

The general economic downturn and sanctions have had a direct impact on vehicle production in the country. In the Iranian calendar year to March 2019, vehicle production totalled just under 956,000, a 38% year-on-year decline. This is very bad news for the wider economy, as the automotive industry represents 10% of Iran’s GDP and employs 4% of its workforce.

IKCO and Saipa, the two largest manufacturers, account for more than 90% of vehicle production and employ 100,000 individuals between them. Across the economy, around 700,000 people work in components production and related industries.

Following the 38% decline in 2019-2019, the first two months of the current Iranian year (March 21-May 21 in the western calendar) witnessed a 42% fall in output to just under 209,000 vehicles. This has intensified the financial strain on the industry, which has asked the government for substantial support in terms of working capital facilities for the supply base. Reportedly as much as 150 trillion rials has been requested, to allow suppliers to buy raw materials and components and enable the completion of as many as 150,000 unfinished cars currently in storage.

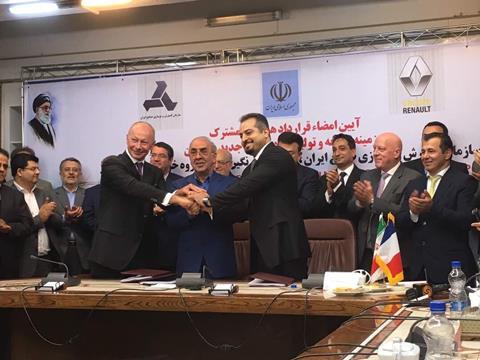

This recent decline in production represents a major turnaround in the country’s automotive fortunes. When Iran agreed a nuclear reduction deal in 2015, investment flowed into the country’s automotive industry – especially from Renault and PSA. In 2016, PSA agreed to build a new plant with capacity to make 200,000 units a year, while Renault signed an agreement to spend $778m on a new 150,000-unit factory near Teheran. The boost to the industry was short-lived; both of these planned factories have now been postponed indefinitely following the re-imposition of sanctions.

Parts shortages have left as many as 150,000 vehicles unfinished and in storage. Carmakers are also accused of hoarding 160,000-300,000 vehicles, pushing up prices

Postponing these new factories is one thing, but on top of this carmakers have taken steps to maintain economic activity and incoming cashflow. The leading brands, notably IKCO and Saipa, are understood to have pre-sold as many as 1m vehicles, with customers paying up front and in full. In Iran, in the absence of other secure assets to buy, and a depreciating currency, many of those with cash have chosen to buy cars, which have been perceived as value-retaining assets in a country where the currency has been in free-fall.

Consumer reaction to paying for cars which are now unlikely to be received is a major concern for the government. This is because the two major producers are partly state-owned, with the government holding 14% of IKCO and 23% of Saipa, at least directly. Other government agencies and bodies are understood to own further shares; press reports suggest that the government will or at least wants to, divest these shares by March 2021.

Fight for supplies in Syria

As late as November 2018, the Iranian government was actually operating a car factory in the Syrian town of Homs. This had opened well before the current civil war, at a time when Iran sought increased economic involvement in the country.

Before conflict broke out, production was reported to be running at just 50-60 vehicles a day, but by the end of 2018 this had declined even further to just three or four units. Moreover, most Homs-made vehicles were in storage as few Syrians had the money for vehicle purchases.

The Homs assembly line had been supplied by sea, as the land border between Syria and Iraq was closed and transport from Iran through Iraq is challenging at best. The current fate of this factory is unknown.

Old cars and problematic parts

Although traditionally reliant on French manufacturers, Saipa has also drawn on Kia technology in recent years, notably for the Pride small car. The Pride has actually been produced in Iran since 1993, using a 1980s version of the car which stopped being made or sold in Korea in 2000. This is not the only out-dated model made in the country, as Saipa also makes the Peugeot 405 which stopped production in Europe as far back as 1997. The 405’s engine and gearbox are also used in IKCO’s Sanand model, the first domestically developed sedan.

In terms of more up-to-date models, IKCO still makes an early version of the Peugeot 206, using locally made parts to avoid getting caught up in the US-led sanctions. An older version of the Citroen C3 is also made by Saipa, although production of this model has recently been very problematic owing to the reliance on French-sourced parts. In addition, until recently IKCO made the Dacia Logan – sold locally as the Tondar 90 or L90 – while Saipa made the Sandero Stepway. Production of these models is now in abeyance as parts can no longer be imported.

The problem of importing parts is a longstanding one in Iran and something the government has been trying to address for some time. Increasing local content has been high on the government’s list of objectives, to boost local economic activity and to reduce the outflow of foreign exchange reserves in buying parts from abroad.

Reflecting this, in November 2017, the government decreed that, by March 2018, cars made in joint ventures with foreign car companies had to have a local content level of at least 40% (a level which several cars made in the UK, for example, would fail to meet). Furthermore, vehicles which did not meet this 40% local content target would be subject to the same 100% tariffs as levied on imported vehicles.

According to the Iran Vehicle Manfacturers Association, as of January 2018, the local content of Iranian-made vehicles varied between 20% and 93%. The Pride is said to have just 13% imported content, although it is noteworthy that it took 25 years to reach 87% local content. The Peugeot 405 is said to have 93% local content, as is the Sanand, while the Peugeot 206 boasts 70%; the more modern 2008 has negligible local content and production was halted following the sanctions.

One piece of positive news has emerged from IKCO, however. The company started production of the Peugeot 301 in July and expects its local content to rise from 60% to 80%. Responsibility for this model is reportedly solely IKCO’s, though quite where the non-local content comes from is not clear.

Meanwhile, before production of the Logan also ground to a halt, its local content had reached 44%, but as of March 2019 there were said to be around 36,000 Logan-based models languishing unfinished in storage areas across the country.

Chinese brands to the rescue?

To overcome the problem of sanctions, Iran has turned to China. IKCO now makes some models based on Chinese models from Dongfeng and Haima alongside its French-based portfolio. These Chinese brands have so far achieved 40% and 20% local content respectively. Similarly, the Chinese-based models which Saipa makes (through collaboration with Brilliance, Changan and Zoyte) have so far managed to achieve only 20% local content.

While production by Chinese vehicle companies had been thought likely to grow, in practice production by Chinese companies has also fallen, by 10% in 2018 compared with 2017. The main Chinese player in Iran is Chery, which has an association with Modiran Vehicle Manufacturing, selling under the MVM brand name.

In addition, Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation has contracted production of its models to FAM, where the MG RX5 SUV is made in Semnan, 180km east of Teheran. While this has begun to reduce the industry’s dependence of the French vehicle companies, there still is a long way to go replace the French base for much of the Iranian automotive industry.

As well as the Chinese moving into Iran, AvtoVaz (in practice part of Renault, but seemingly able to enter Iran without Renault facing US sanctions) and truck manufacturer Kamaz have also begun to enter the Iranian market. At the moment this is achieved through exports from Russia, but local manufacturing may well take place in due course. Kamaz has already established joint ventures in nearby Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, with supply chains which could be extended to Iranian operations.

Mena: Infrastructure, policy and regulatory developments

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

Currently reading

Currently readingIran’s automotive industry left to rust

- 7

- 8

No comments yet