FCA–PSA fusion: first of the electric shock waves?

The merger attempt by FCA and PSA will be complicated but makes economic and operational sense, including for supply chain management and logistics. Whether or not it goes ahead, more consolidation is likely as the automotive industry gears up for electrification

The pace at which PSA Group and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles appear to have agreed a deal to merge and create the world’s fourth largest carmaker is remarkable, with an agreement in principal hammered out in just a few days.

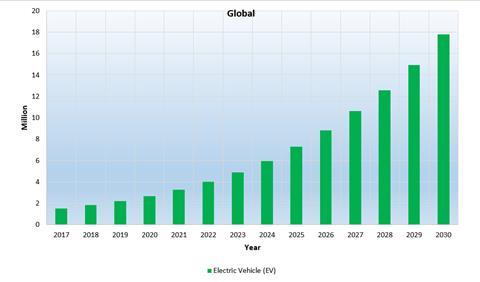

Although hurdles remain before a final merger, that speed suggests a growing urgency across the automotive industry. In the face of mounting pressure to invest in new technology, notably electrified powertrains, expensive fines over emissions, and the risk of a prolonged slowdown in global vehicle sales, traditional automotive players need to gain even more economies of scale and pool risk to make these transitions – if not to survive (download our latest foreast and analysis of global powertrain shifts below).

A speedy merger deal was something of a sprint following a long, uphill marathon that anticipated how tough things could get for the automotive industry. Back in 2015, FCA’s then CEO, the late Sergio Marchionne, made his ‘Confessions of a capital junkie’ plea, warning manufacturers against independently developing expensive technology, such as powertrains, that would eventually be commoditised. Since then, the carmaker has sought merger partners, with overtures, rumours (and rejections) with the likes of General Motors, Hyundai, Volkswagen Group and Chinese OEMs.

Earlier this year, a merger between FCA and Renault proved too complicated and was abandoned.

PSA, meanwhile, bought Opel/Vauxhall from GM two years ago and its chief executive, Carlos Tavares, has courted more candidates for acquisition. Earlier this year he said that PSA could buy Jaguar Land Rover from Tata (Tata said it will not sell). Tavares has also been frank about the costs and challenges of tough EU emission targets, as well as his plan to bring PSA back to the North American market.

A combined PSA-FCA does not solve all of the problems across both companies, including weaknesses in China and Asia, or their current lack of advanced electric powertrain technology. And navigating interests between French, Italian and American shareholders and governments – especially in the current mood of economic nationalism – will not be plain sailing.

But the merger certainly makes sense, bringing together two brands with strong profits in North America and Europe, and providing more opportunity to share platforms, mitigate fines and pool investment in electrification. With expectations for sharp growth in a variety of electrified powertrains over the next decade, few companies will be able to go it alone. We think it a sign of much more to come.

Profits today, gone tomorrow?

We forecast a tough period over the next few years for the automotive industry (read our global forecast and outlook here). A softening economic climate, trade tensions and political instability have contributed to declines in global vehicles sales over the past two years. Most OEMs have issued profit warnings as demand has weakened in virtually every major region and emerging market. At the same time, investment is ramping up for electrification, autonomous driving, connectivity and shared mobility models.

And yet, sales might not recover in the short term. We don’t anticipate any significant momentum until well into the next decade. Profits are at risk.

At 4-8%, carmakers and tier suppliers have lower average operating profits than most other industries. This has in part been because of high capital investment requirements, along with highly competitive and often fragmented markets. A low return on capital employed also makes it difficult to justify the technology and manufacturing tooling required for an electric future, especially as electric vehicles are much less profitable for most OEMs than vehicles with standard internal combustion engines.

PSA and FCA both exemplify many of the current challenges. In 2018, FCA achieved revenues of €110.4 billion ($123.3 billion) with operating income of €4 billion, an operating margin of just 3.7%. It has recently performed better, with third quarter profits in North America surpassing 10%. Its European results, however, remain in the red, whilst the company has struggled in most other global regions. With the economic outlook in the US weakening, it is understandable why FCA is keen to seek alliances.

PSA reported revenues of €74 billion last year with operating income of €4.4 billion for a margin of 5.9%, including a slim profit for Opel/Vauxhall for the first time in 20 years. This year, PSA has defied industry averages with operating margins of 8.7%, supported in part by Tavares’s successful cost efficiency, a fast transition to new, consolidated platforms and improvements in reducing vehicle inventories. However, further cost efficiency savings are thought to be minimal, and PSA’s primary markets in Europe are in decline.

Size has long mattered for the automotive industry to gain economies of scale in purchasing, engineering and manufacturing. But rarely have so many factors aligned at once to challenge the sector’s major players, and with it the requirement to share in investment and risk.

M&A Motors

Despite the challenges of a merger, we believe that the climate of technology change, slowing sales and uncertainty will lead to more formal and informal consolidation in the automotive sector. OEMs are likely to make similar strategic moves. Even those as large as Ford and General Motors lack the scale to compete in the race to electrification. By 2030, we expect that the current 20 major OEMs could be reduced to 10-15 key groups.

Over the next decade, we also expect more joint ventures, technology exchanges, platform sharing, alliances and partnerships to increase cooperation in the industry. That could also include OEMs purchasing minority stakes in other companies, as is becoming prevalent. Toyota recently increased its stake in Subaru. There have also been reports that VW could purchase a stake in Tesla, although the companies have denied it.

A similar transition is also occurring amongst tier suppliers seeking vital economies of scale. Recently, Honda Motor Company and Hitachi Automotive Systems agreed to merge four of their car components businesses including Keihin Corp, Showa Corp. and Nissin Kogyo Co. to create a supplier with sales of around $16.5 billion. In some cases, OEMs are also bringing the supply of some key components back inhouse, at least partially. Tesla is developing battery Gigafactories with Panasonic, for example, and VW has a similar venture with Northolt for batteries.

Ultimately, the FCA-PSA merger would place the companies in a much stronger place than would no merger. The pooling of resources, cost savings, purchasing power and economies of scale would give the combined group the best chance to compete in the race to electrification and other next generation technologies.

The interesting part will be to see whether this new Transatlantic tie-up triggers a new wave of automotive M&A activity and industry consolidation.