Packaging automotive parts for international shipments is subject to strict phytosanitary regulations on pest control. Magna International’s Bridget Grewal details the cost of contamination and the strategies for treatment.

There are many factors governing the international shipment of automotive parts and one of the most important is packaging. The automotive sector has unique challenges because of its diverse product range and global networks. Components are often moving across international boundaries multiple times and the packaging used is designed with very specific requirements in mind. Not only must the packaging accommodate a wide range of component sizes of specific dimensions and often high value, they must be moved efficiently and subject to considerations of weight, fragility, material composition, and the potential for vibration and shock. There are also environmental factors to consider such as temperature and humidity.

One of the other crucial factors sometimes overlooked is the requirement for compliance with rules on phytosanitation. That refers to the control of plant diseases and the spread of environmentally destructive pests between locations, regulated by the globally recognised International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures publication 15 (ISPM 15), which is governed by the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). Everything shipped using wooden pallets or other wooden dunnage has to be in compliance with ISPM 15. The regulation specifies appropriate sanitation procedures for coniferous softwood and non-coniferous hardwood that is used as raw wood packaging materials, including pallets. That sanitation procedure involves heat treating the wood packaging (see box on approved treatments) and stamping a mark of compliance on it that is scanned by agents during the import process.

“Any piece of solid wood, whether it’s dunnage, whether it’s bracing on the truck, whether it’s the pallet, or what it’s inside the box – a corrugated box with some stanchions in there to help support it, for example – all of that wood needs to be heat treated first and then marked,” explains Bridget Grewal, director of packaging continuous improvement at tier one supplier Magna International.

Bridget Grewal, director of packaging continuous improvement at Magna International, will be speaking at our 25th Automotive Logistics & Supply Chain Global conference, taking place 23-25 September in Saint John’s Resort, Plymouth, Michigan.

Grewal will discuss how to advance sustainable packaging solutions as part of our special packaging focus at the event, which will also feature discussions about safe, sustainable and scalable packaging for EVs, innovation through packaging for smart material flows, and opportunities for container management with data and sensor technologies.

For more information on the agenda, and to register now to secure your spot, click here.

Without that mark the consignment can be quarantined, which can either mean all of the parts are sent back to the country of origin, or the consignment is repalletised on verified material and admitted while the packaging is returned to the country of origin.

A consignment that is quarantined at the point of entry until it is repackaged and has the correct paperwork can delay delivery or production materials for months.

Approved treatments

Heat Treatment (code HT): Wood packaging materials are subjected to a heat chamber for a required minimum of 30 minutes once the core temperature of the thickest component reaches 56C.

Heat treatment using Dielectric Heating (code DH): Using a similar process microwaving. Wood packaging material is exposed, throughout the entire profile of the wood, to microwaves, at 60C, for at least one continuous minute. For this to comply with ISPM15, the 60C temperature minimum must be reached within 30 minutes of the beginning of the application.

Methyl bromide fumigation (code MB): A more hazardous and expensive method, MB fumigation requires that wood packaging materials be exposed to MB gas for over 24 hours at a given temperature. The use of this method must be approved by the National Plant Protection Organizations (NPPO).

Cost of contamination

The cost of using non-compliant packaging is steep. The absence of an authorisation stamp indicating the packaging has been treated according to ISPM 15 can mean a standard cost of $250,000.

“Whether they rejected the material, whether they quarantine the material or they let you repack the material, you’re going to get a fine,” says Grewal.

What is more, being found in violation means subsequently having to show the customs authorities of the importing country that you are working hard to be in total compliance. If a company does not do this it, the cost continues to rise.

“Each time you violate, the charges go higher and higher because they want you to stop, and in America not adhering to phytosanitation rules can be considered an act of terrorism,” adds Grewal.

A company found to be non-compliant may be subject to the inspection of every single shipment it makes. Any failure will stop a shipment and total compliance with all shipping requirements is closely monitored. One stray dandelion seed could potentially cost a blacklisted company more than a million dollars. For the supplier shipping automotive parts, ensuring the wood meets the regulatory requirements means direct inspection of the packaging supplier.

“If you have to ship on a solid wood packaging to get the part there safely, then you have to go and audit plants and only buy from that audited wood supplier location,” Grewal reiterates.

Counterfeit pallets

Fines will also increase if the packaging is stamped with counterfeit heat-treatment symbol, which makes auditing the packaging suppliers all the more important. Suppliers of parts need to ensure that their packaging suppliers are properly compliant and not resorting to counterfeit stamping. Counterfeit classification is hard to police in certain countries, such as Mexico and Turkey.

“The counterfeit pallets could come from any system that doesn’t heat treat the materials at the mill,” explains Grewal. “So, in the US and Canada, when the mill cuts the wood, they heat treat it right there. And then they send the heat-treated wood to the pallet manufacturer and stamp it with their own stamp to say we know that this is heat treated because they did it at the mill.”

What shippers also have to be wary of is the substitution of properly heat-treated packaging with kiln-dried wood, which is a much slower method of heating treating that does not use high enough temperatures to be able to kill the all of the potential pests in the wood.

”If you have to ship on a solid wood packaging to get the part there safely, then you have to go and audit plants and only buy from that audited wood supplier location” – Bridget Grewal, Magna International

One-off shipments

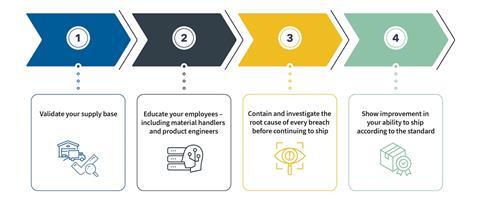

With mill-treated wood that is properly validated being used in regular production of the pallets, the risk of falling foul of contamination or counterfeiting is significantly reduced. To avoid shipping a pallet that has not been heat-treated for international shipments, Magna has trained its material handling people to doublecheck inbound and outbound packaging for the proper stamp.

Where trouble can arise is in one-off shipments, such as when product engineers send samples overseas and pull any pallet from the production plant to ship them, wrongly assuming they are all the same. Side-stepping the proper material-handling checks and sending the consignment off leads to error. In fact, one-off mistakes of this kind account for more than 50% of the custom failures. To avoid problems here, Magna trains all of its part engineers to be alert to the packaging rules and requirements.

“If we buy equipment and the process engineer goes to that supplier location where the equipment’s going to do its first runoff, then we put it in their scope of work that they have to check the packaging when they’re on site,” says Grewal.

That includes directing them to only use certified or audited pallet-making plants and making them aware of why heat-treated pallets are more expensive than non-heat-treated ones because of the costs of the process. For example, paying $10 for a non-heat-treated pallet rather than $15 for a heat-treated pallet is an indication of not following the supplier and customer guidelines, and being in violation of both, according to Grewal.

Exemptions and alternatives

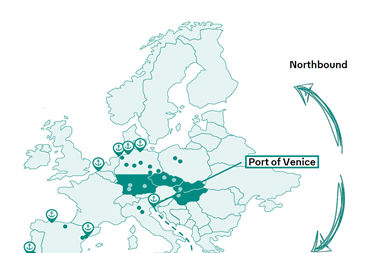

In North America there are currently phytosanitary exemptions for shipments between the US and Canada because the species of bug are so similar there is either no risk, or only a very remote one, that trees could become contaminated. That is not the case for shipments from Mexico to either of its North American neighbours.

That is similar to the European Union, in which member states are exempted from having to use heat-treated pallets, though they still have to be rigorously cleaned for such things as seed debris or mould.

Looking for alternatives to solid wood packaging to get around the phytosanitation requirements is not as straightforward as it may initially seem. Oriented strand board (OSB), which is made of layered and compressed wood chips that are glued together, cannot be recycled because the adhesive jams up the recycling equipment. That raises the cost of disposing of the pallets in the destination country.

Five years ago, plastic would have also been too expensive, more than double what a wooden pallet costs. However, companies are now making single-use, thinner plastic pallets, which are less expensive. There are also a range of alternative organic materials now available out of which to make pallets, such as hemp, mycelium or bamboo.

“These other materials make the pallet cheaper and they use water-soluble glue so you can recycle after it arrives,” notes Grewal.

Returnable pallets are not that often used for cross-ocean deliveries because of the cost incurred in getting them back, though pooling providers such as Chep offer international returnable packaging services. The system is more prevalent in Europe, not so much in the US, but Grewal indicates that the industry is evolving and once sensor technology is in place to track them tier one shippers may be able to use returnable containers across the ocean.

“I think that phytosanitation, sustainability and sensor technology are linked together,” says Grewal. “If we can use plastic or metal returnable containers and get away from single use wood, [and] put a sensor on that – BLE, GPS or RFID – then we would be able to get it across the ocean and back and we wouldn’t go through that attrition that we usually do – less environmental contamination, less waste and less loss.”

No comments yet